Theatre-related reading: Bring the House Down, Theater Kid, Happy Days

I review Charlotte Runcie’s very entertaining novel about a scandal at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival

The Edinburgh Fringe, the granddaddy of all Fringe festivals, is in full swing right now. (If you’re lucky enough to be there, please check out Rebecca Perry’s Confessions of a Redheaded Coffeeshop Girl and Hannah Moscovitch’s Red Like Fruit. The latter, which I reviewed back in May, just won a prestigious Edinburgh Fringe First from The Scotsman.)

Charlotte Runcie’s very entertaining first novel Bring the House Down (Rating: ✭✭✭✭) is set entirely at the festival, and it made me want to experience all the action firsthand. One of these days I hope to get there.

Alex Lyons is the London-based chief theatre critic of a well-known British newspaper — one “considered by some people to be the last remaining newspaper of decency, and by other people to be a rag of unforgivable bias.”

The book opens as Alex writes a one star review of a dreadful-sounding ecological-themed solo show called Climate Emergence-She, by an American expat writer named Hayley Sinclair. After filing his copy, Alex sees the unsuspecting writer/performer in a bar (she has no idea who he is), chats her up, and takes her back to his flat.

When Hayley reads the pan the next morning, and realizes she just slept with the guy who wrote it, she becomes livid. She soon changes the name of her show to The Alex Lyons Experience. At first, she reads the review out to audiences, with vitriolic commentary, but then she opens up the show to be a forum for others who have suffered similar bad behaviour from the man: exes, emerging artists who gave up promising careers after receiving bad reviews, etc.

The show quickly becomes one of the festival’s runaway hits, and Alex is on his way to getting cancelled.

Rather than narrate the novel from Alex or even Hayley’s point of view, Runcie lets us watch the drama unfold from the clear-eyed perspective of Sophie Ridgen, a junior culture writer at the same paper where Alex works.

The two are staying at the Edinburgh flat rented by their newspaper to cover the festival. While Alex is busy going to five or six shows a day and then filing his reviews, Sophie attends art exhibits to do the same thing. She is happy to be covering the Fringe, having recently come back from maternity leave. She also writes obituaries, often of people who are very old or ill, so they’re ready to run when the person dies.

Sophie is glad to be away from her London home for a while — she and her academic husband, Josh, have reached a plateau in their relationship, though she misses her 14-month son Arlo — to concentrate on journalism.

But her enjoyment is interrupted when the scandal breaks. She has always looked up to Alex as a more senior arts journalist, but has her judgement been clouded by his reputation, intelligence and glamour? (He is the son of one Dame Judith Lyons, a well-known aging actress and director. Alex grew up going to plays, having theatre and film folks around his home, and immersed in industry gossip.)

The book is at its best when Runcie — a former arts columnist at The Daily Telegraph who’s also written for The Times and The Guardian — describes the arts beat. There are painfully accurate descriptions of listicles, bad Fringe plays, mildly debauched cocktail parties. She also knows how quickly copy has to be turned around.

Runcie is incredibly shrewd about how the internet changed reading habits — and publishers’ and editors’ bottom lines. And there are extended musings on the star-rating system. Is a 3 star (out of 5) review fence-sitting? No, as my colleagues and I used to say at NOW Magazine, it’s recommended! (Joshua Chong at The Toronto Star wrote about the star rating system a few months ago.)

While Sophie’s personal story slows down the mid-section of the book, she does make a balanced, even-handed narrator. And she seems to be at a crossroads herself — in her life, as well as her career. You get the sense that she’s learning from what’s happening around her. Her description of a play about the migrant crisis is great writing. Every theatre critic has seen this kind of show. But how to write about it?

Where Runcie excels is her questioning the ethical and humane implications of arts criticism. Did Alex behave badly by doing what he did? If so, did he deserve what happens to him?

Much to think about as you stand in line at a show, Fringe or otherwise.

Bring the House Down is published by Penguin Canada Random House. Congratulations to Beth G., Lindsay L., and Victoria L., who each won a copy of the book in a recent So Sumi contest. I asked which Toronto Fringe play was heading to the Edinburgh Fringe — with the hint that it won a Patron’s Pick Award. Their names were randomly chosen from the correct answers.

As producer Derrick Chua correctly pointed out, it was a bit of a trick question, since two shows from Toronto were Edinburgh-bound: Perry’s Redheaded Coffeeshop Girl and Duane Forrest’s Bob Marley: How Reggae Changed the World. Both are currently there now.

What else I’m reading

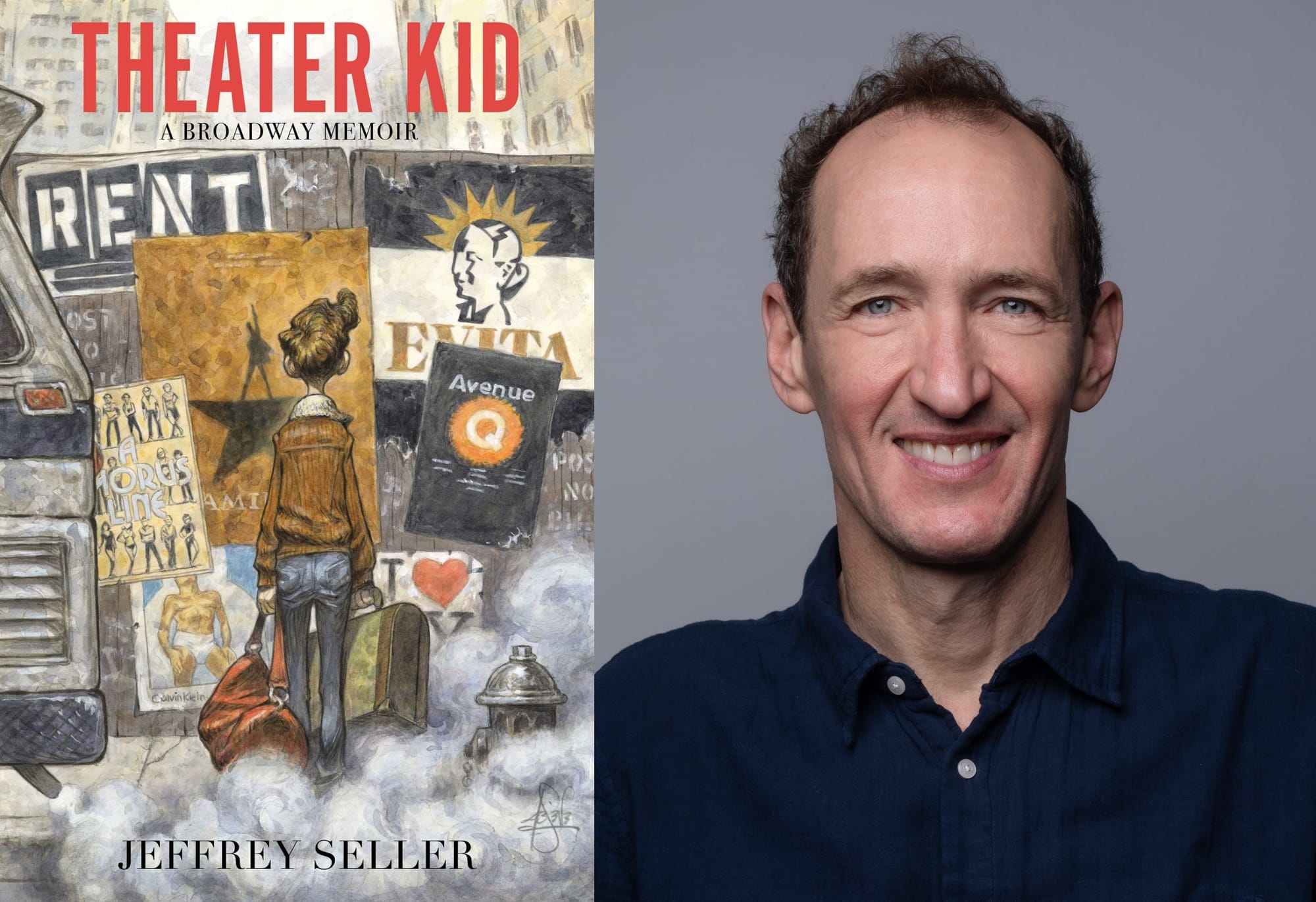

I love theatre memoirs, especially ones that give me background information on shows that I already know and like. Jeffrey Seller’s Theater Kid (Simon and Schuster) recounts his modest background as an adopted kid who grew up closeted in a dysfunctional family outside Detroit and his journey to getting to New York and eventually producing Rent, Avenue Q and Hamilton. I’ll write a review when I’m done.

I just finished reading Han Ong’s lovely short story “Happy Days” in The New Yorker. Ong, a playwright and former MacArthur fellow, imagines an Off Off Broadway production of Beckett’s Happy Days starring an elderly Chinese actor, Matthew Lim, as the play’s female lead, Winnie.

Because of the Beckett estate’s notoriously strict rules about casting and production details, the company is worried that they will be shut down — so they announce that Matthew will be replacing another company member, Aira, and ask audience members not to spoil the surprise on social media posts. (Aira, who starred in a gender-reversed production of King Lear decades earlier, does go on as Winnie a few times.)

Han creates a wonderful world of aging downtown, indie art makers. And his insights into the play and this great role — best known, of course, by the image of a woman being buried up to her neck — are profound. There are also subtle suggestions of Matthew’s childhood growing up in Chinatown, being self-educated, losing friends and colleagues in the early days of the AIDS crisis.

Ong, a former actor himself, reads the story in the New Yorker’s The Writer’s Voice podcast. He also discusses the story with editor Deborah Treisman here.

Consider it background for when the great Nancy Palk takes on the role of Winnie next year at Soulpepper.