Stratford’s new Anne of Green Gables is full of wonders

Plus a review of another Canadian classic, David French's Leaving Home, and two Luminato shows

I’m glad I didn’t know too much before seeing Kat Sandler’s brilliant new adaptation of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s classic Anne of Green Gables (Rating: ✭✭✭✭✭) at the Stratford Festival.

Sandler, of course, is the gifted, prolific contemporary playwright whose edgy, funny, fast-paced works like Bang Bang and Mustard have resonated with summer festival and mid-sized theatre audiences alike.

What could she add to the beloved tale of the feisty red-headed orphan who’s grudgingly taken in by a pair of older siblings in late 19th century Prince Edward Island?

Turns out quite a lot.

Sandler, who also directs, has devised a clever idea to frame the play. Members of a contemporary book club have come together to discuss the novel, and soon, with a bit of whimsical stagecraft, they begin bringing the story to life onstage. When there’s no actor to play a character, or a horse, one of them jumps in.

And when someone doesn’t know something — for instance, the antiquated architectural term “gable” in the title, or what a “cordial” is — another will help explain. All of this is written and directed by Sandler with a minimum of fuss for maximum clarity and theatricality.

After establishing this set-up, Sandler and the talented ensemble begin telling Montgomery’s tale. 11-year-old Anne (Caroline Toal) — spelled with an “E,” of course — is not the boy that siblings Marilla (Sarah Dodd) or Matthew Cuthbert (Tim Campbell) have wanted to help out on their farm. But gradually she wins them — and the fictional town of Avonlea — over with her spunk, intelligence and imagination.

That last word, “imagination,” is key to the story — and this production. Anne dreams up elaborate fantasies and voices every one, perhaps as a coping mechanism. Which makes you think: What is watching a play, in the end, but a sustained use of the imagination?

Sandler faithfully follows the familiar beats of the story — which has been adapted dozens of times. Anne flies into a rage after busybody neighbour Rachel Lynde (Maev Beaty) criticizes her appearance (love the red lighting that designer Davida Tkach has provided here). She befriends Diana Barry (Julie Lumsden). In school, she has a complicated, competitive relationship with Gilbert Blythe (Jordin Hall). Her first teacher, Mr. Phillips (Josue Laboucane), keeps misspelling her name and is contemptuous of her humble origins; her second, Miss Stacy (Jennifer Villaverde), encourages her writing.

Most important is the question of whether Anne will ever feel like she belongs in the Cuthbert household. The taciturn Matthew is quickly charmed by her; the more practical, straight-laced Marilla is more resistant.

Sandler offers up many lovely touches that will make you see the material in a fresh way. The simple use of some flowering branches — held in an arch by the chorus — brings the locale to life in a way an elaborate, ostentious design never could. (Joanna Yu is the talented set and costume designer.) I love how Hall’s Gilbert unsuccessfully tries to establish his authority at school by placing his foot on a chair in the classroom, or how Steven Hao so gamely and casually transforms from a reader into one of Anne’s friends. I also like how, as the seasons change, Laboucane comes in to announce that fact with a little flourish.

The most radical shift in the storytelling comes in the second act, however. But it arises so naturally — Miss Stacy asks Anne to dig deeper to really explore her current life — that it feels just right. This is the section of the play that ought to excite young viewers; it illustrates how the most timeless art doesn’t necessarily rely on its period details but rather its human truths.

Dodd and Campbell are beautifully cast as the Cuthbert siblings, never winking at the audience or milking a scene for easy emotion. Both have a gravity in the way they hold themselves, walk and talk that anchors them and gives them solidity.

Did I ever imagine that Toal, a frequent performer with The Howland Company, would be convincing as an 11-year-old girl and then young woman? Absolutely not. But she is the Anne of one’s dreams: spirited, passionate, self-dramatizing yet ultimately in search of fairness. Like Anne, she will capture your heart.

Lumsden brings warmth and humour to her bestie Diana, while Beaty — who besides playing Rachel Lynde also kickstarts the play as the eager leader of the book club — is full of surprises that keep paying off. I’m not sure if this detail comes from Sandler or Montgomery, but the way even Anne’s antagonists — like Rachel and, to a lesser extent, mean girl Josie Pye (Helen Belay) — are given subtle character shading in the play’s second half is hugely satisfying.

An early exchange between Marilla and Matthew made me fall in love with this play, which I hope gets picked up for a remount in the city.

The former, upset because she wanted a hard-working boy to work on the farm, says, “What good would she be to us?” To which her brother replies, “Maybe we’d be good for her.”

In today’s world, where strangers and outsiders are often demonized and unfairly blamed for all of society’s ills, and life is merely a series of transactions, that’s a beautiful, inspiring and humane lesson.

This remarkable Anne of Green Gables is full of them.

Anne of Green Gables continues at the Avon Theatre, 99 Downie St., Stratford, until October 25. See details here.

Revisiting another Canadian classic

Nearly a decade ago, Ravi Jain directed a pared-down, exquisite reimagining of David French’s play Salt-Water Moon. It won awards, got remounted, toured the country.

I wish some of that magic had been applied to Halifax company Matchstick Theatre’s more traditional staging of Leaving Home (Rating: ✭✭), an earlier play in French’s Mercer family cycle, one that — shortly after it premiered in 1972 at the Tarragon — became a landmark in Canadian theatre.

The story is classic kitchen sink drama. On the eve of the shotgun wedding between 17-year-old Bill Mercer (Sam Vigneault) and his Catholic girlfriend Kathy (Abby Weisbrot), the family of four — father Jacob (Andrew Musselman), mother Mary (Shelley Thompson), sons Bill and Ben (Lou Campbell), plus Kathy — have gathered for a rehearsal dinner.

Besides their food, they’re all set to dine on a bunch of secrets. Ben, for instance, who graduated from high school but didn’t invite his loutish dad to the ceremony, is about to move out and live with his brother and his about-to-be-sister-in-law. Kathy, meanwhile, has news that she worries will get Bill to call off the wedding. And then there’s the matter of the accident that Jacob suffered months earlier, and the explanation of how the family has been getting by since then.

There are very few surprises in either the script or director Jake Planinc’s production, which relies more on the gritty realism of Wesley Babcock’s set and the in-the-round staging than on any dramatic or psychological plumbing of these characters. Also: apparently the play is set in 1950s Toronto, but where is the evocation of the city back then?

The most intriguing thing about this production is the casting of non-binary actor Campbell in the role of the author stand-in Ben, which perhaps is meant to underscore Jacob’s toxic masculinity.

Unfortunately Campbell, so memorable in their anarchic Fringe 2022 play Prude, fails to bring much depth or nuance to Ben; for that matter, none of the younger actors seems to have a firm grasp on their character.

Thompson fares better, especially as the play progresses (she also has a lot of tasks to do, which helps pass the time). But the standout is Musselman, whose short-tempered, proud Jacob is full of contradictions that make him alternately frightening and pitiable. The most memorable scenes are the ones where you can glimpse what drew this couple to each other so many years before.

It’s telling that French’s play, often cited as a Canadian classic, is rarely revived. The last professional production was nearly 20 years ago at Soulpepper, directed by Ted Dykstra, who’s the chief engineer of the venue hosting this current staging, Coal Mine Theatre.

Until someone else comes along to do it justice, this revival makes you understand why.

Leaving Home continues at the Coal Mine Theatre, until June 22. See details here.

Luminato x 2

One of the benefits of a festival like Luminato, which closes this weekend, is its international scope.

Once upon a time, Toronto theatregoers used to be able to see lots of theatre from other countries at Harbourfront’s World Stage series. In addition, there were more presenters of global work. Now it’s much rarer. But in 19 years, Luminato, especially before its funding issues, helped fill some of that gap. Let’s hope more international programming continues under new artistic director Olivia Ansell.

Of the two international shows I saw at this year’s festival, I enjoyed Peruvian company Teatro la Plaza’s innovative Hamlet (Rating: ✭✭✭). The unique production — presented in Spanish with English surtitles — was less an adaptation of Shakespeare’s classic than a series of scenes involving eight actors living with Down syndrome interacting with the play and its existential themes.

Taking King Hamlet’s command to his son to continue his legacy literally, the actors and playwright/director Chela De Ferrari explore the idea of what they are passing on.

In this context, Polonius’ “Neither a borrower nor a lender be” speech becomes a passionate, problematic warning. “Your children will be imbeciles,” he tells his daughter. “You’re not like other girls.”

One of the most moving sequences sees all the female actors, who’ve written down their dreams, mourning Ophelia’s death as well as the end of their dreams.

Sometimes a word or phrase will take on a new meaning, such as when an actor who has an occasional speech impediment delivers the phrase “Words, words, words.” Indeed.

The show’s most prolonged sequence is inspired by the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, and it ranges wildly in tone and texture. One actor tries to mimic the physical gestures of great Hamlets of the past, while another interviews Ian McKellen (via video chat) on the demands of the role. Best is when the actors take the spirit of the long passage and channel it into rapping.

Some of the themes, while powerful, soon become repetitive. But how many productions of the Danish play end with an audience participatory dance?

I was less impressed with Tim Crouch’s An Oak Tree (Rating: ✭✭), which comes to the festival as part of the work’s 20th anniversary. The rather contrived premise is inspired by an actual tragedy in which a 61-year-old man whose daughter has been killed in a car crash visits a magic show put on by a hypnotist — the same man who ran over his daughter years earlier.

The novelty is that that man, named Andy, is played by a new actor each time out, one who’s never seen the show before. The show is entirely scripted, but Crouch, who also plays the hypnotist, either tells the actor what to say, via a microphone and headset, or a written script, or (least effective) simply by telling him or her to repeat things.

While this casting adds some excitement, it also adds fussiness and a potential lack of clarity to an already confusing narrative about grief, guilt and memory. The story would be heartbreaking told literally; to hear it told in this fragmented, piecemeal fashion somehow lessens its impact.

Actor Rebecca Henderson (Russian Doll) was the Andy at the matinee I saw, and she navigated the various scenarios skillfully and with great sensitivity. But even she couldn’t make up for the forced set-up and the vagueness of the central metaphor.

The most powerful sequence comes near the end when Crouch and Henderson, accompanied by the aria from Bach’s Goldberg Variations, deliver monologues side by side, recounting their characters’ actions before the fateful event. Simple. Effective. Non-gimmicky.

An Oak Tree continues until June 22 at the Jane Mallett Theatre (27 Front East). See details here.

Forgiveness preview

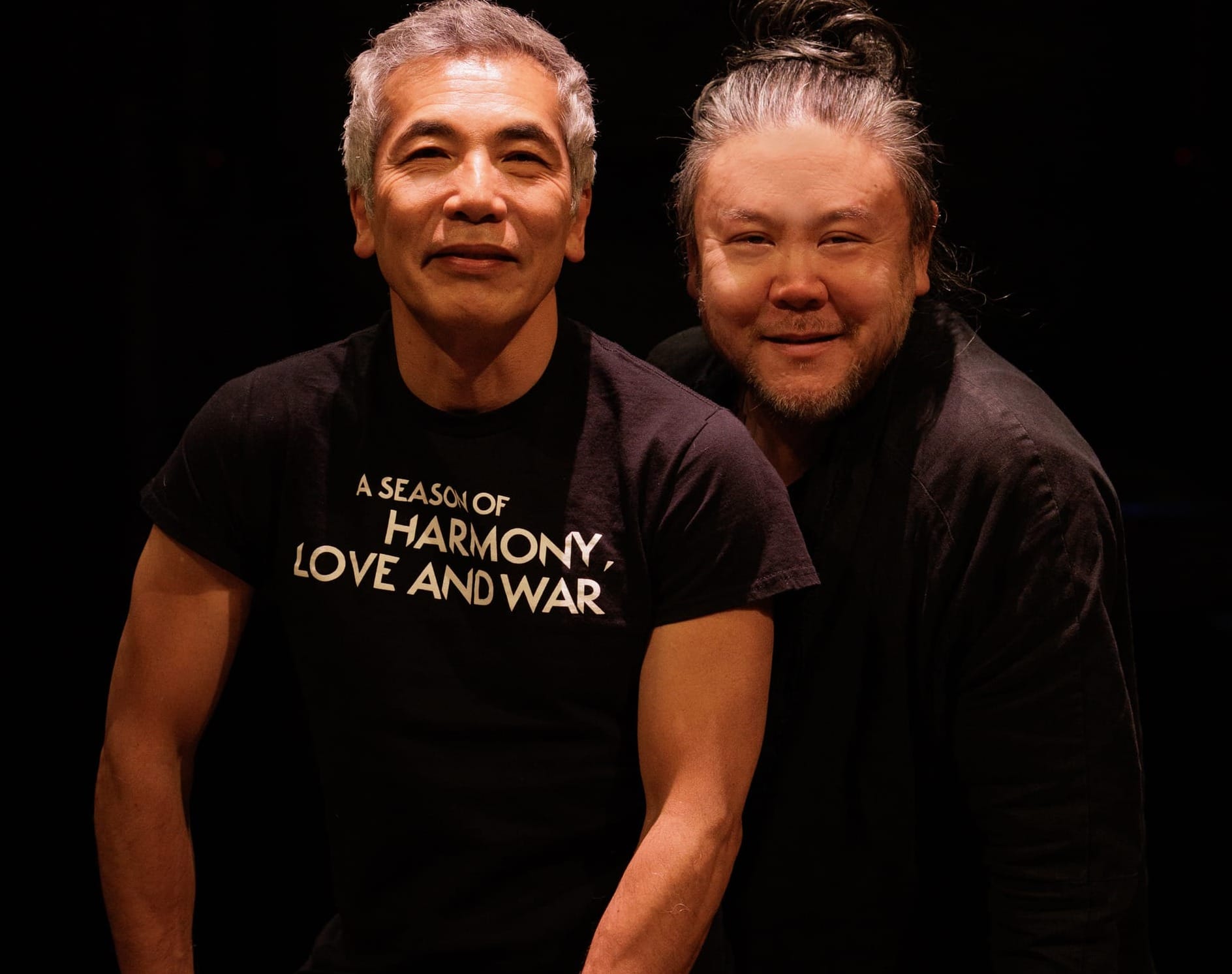

Forgiveness, Hiro Kanagawa’s Governor General’s Award-nominated adaptation of Mark Sakamoto’s memoir, opened earlier this week at the Stratford Festival. A couple of weeks ago I got to chat with both Kanagawa (Shogun, The X Files) and director Stafford Arima.

Here’s a link to that article.

I’m catching up on four plays at the festival next week, but hope to catch Forgiveness after the Toronto Fringe (July 2 to 13) ends. Speaking of the Fringe, look for my preview piece here early next week. I’ll also be filing reviews at The Toronto Star and Parton & Pearl.