Shakespeare x2: Macbeth and The Winter’s Tale at Stratford

One of these productions is exquisite, while the other is full of sound, fury and mock motorcycles, signifying not a helluva lot

I saw these Shakespeare productions several weeks ago during a 36-hour, four show trip to the Stratford Festival, but both stay with me pretty clearly. Alas, they were memorable for different reasons. One was exquisite; the other, well, wasn’t.

First, the good production. The Winter’s Tale (Rating: ✭✭✭✭) can be a difficult play to produce. It begins as tragedy, with a jealousy plot line and a series of deaths that seems ripped straight out of Othello. Then, after the appearance of a character named Time (Lucy Peacock) and a flash forwarding of some sixteen years, it transforms into a pastoral comedy and romance, with one of the most moving conclusions in the entire Shakespeare canon.

I’ve seen fine productions of the play before, notably the Groundling Theatre’s inaugural production at one of Coal Mine’s earlier venues.

Incidentally, that show was directed by Graham Abbey, who’s a lead in this Stratford version. Consequently, Abbey knows the play thoroughly, as he demonstrates in his grounded and deeply felt performance as Leontes, King of Sicily, who believes his pregnant wife, Hermione (Sara Topham), and his childhood friend Polixenes (André Sills), King of Bohemia, have had an affair and that the unborn child is Polixenes’.

Because the play isn’t frequently performed, I’ll hold off on further synopsis, except to say that some characters die, others escape to Bohemia, and time — that great leveller — gives people a chance to repent and atone for their actions. Antoni Cimolino’s production opens with an enchanting tableau that feels like a fairy tale, or at least a Cirque du Soleil show, and that’s the spirit we should take it in.

Cimolino and his design team allow for maximum contrasts between the formal world of the Sicilian court, where people are draped in rich, ornate dark fabrics, and the sunny feel of Bohemia, where there’s a lighter, gentler feel to both the costumes’ looks and weight. (Francesca Callow is the costume designer.) Michael Walton’s evocative lighting also reflects the difference between these societies, and it is absolutely essential in making the final scene so haunting.

The director stages the play so it never feels cramped or limited on the long, narrow thrust playing area of the Tom Patterson Theatre. All of this lets us savour the nuanced performances by Abbey, Topham, Sills and Tom Rooney (as an ambassador to the King) as the drama quickly escalates in the first act.

I’d never fully realized what a great role Paulina — a Sicilian noblewoman who defends Hermione — is. But Yanna McIntosh seizes hold of it and expresses a huge range of emotion, climaxing with the devastating line to Leontes, after he’s brought about his own personal tragedy: “Do not repent these things, for they are heavier than all woes can stir. Therefore betake thee to nothing but despair.”

In Bohemia, the pacing slows down a little. After the weightiness of the first half, it’s a relief to witness the gentle clowning of Tom McCamus and Christo Graham as a simple shepherd and his son, as well as Geraint Wyn Davies as a roguish pickpocket who has an unexpected role in the play’s ultimate outcome.

You can even see how Sills and Rooney let loose and relax in this setting. Sills’ King and his friend are disguised to spy on the burgeoning romance between Polixenes’ son, Florizel (Austin Eckert), and his mysterious and noble-seeming girlfriend, Perdita (Marissa Orjalo), who share a warm bond.

The play is not without its problems, including the rather ham-fisted way the narrative returns to Sicily, and a key scene in the dramatic resolution being presented as exposition. Also, what did Rooney’s ambassador do with himself for over a decade and a half?

But as its title suggests, this is a fantasy, something to be told on a long winter’s night. So logic doesn’t apply. In Shakespeare’s later plays, wrongs can often be righted and sins can be forgiven. Most importantly, lost children can be reconnected to their families, something that must have given comfort and peace to the author, given his own personal losses.

Perhaps it’s because of the uncertain times we’re in right now, but this production hits the right note of hopeful, humane optimism. That’s the thing about great art; it can work on a healing, subconscious level, something beyond the literal.

The Scottish play on wheels

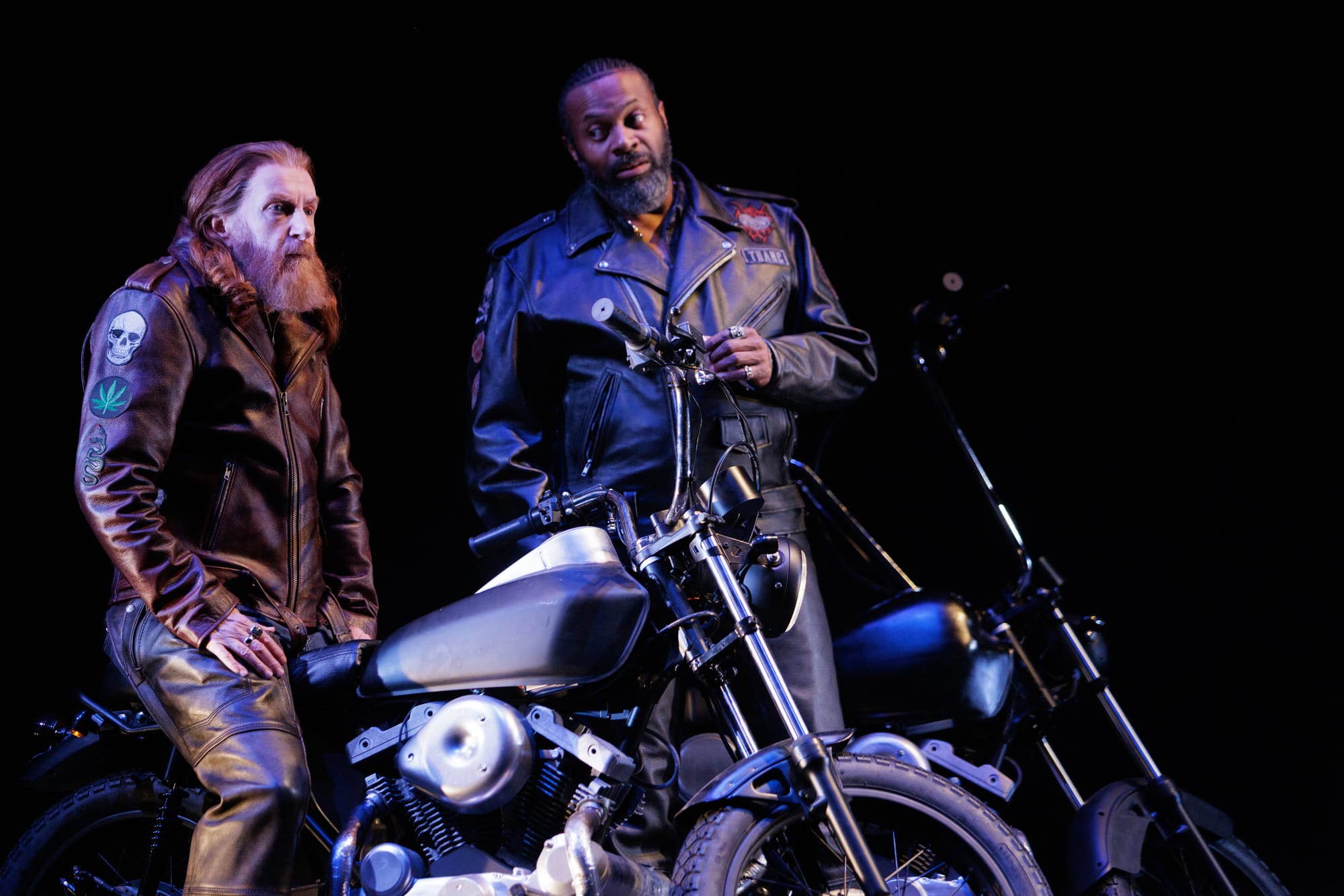

Robert Lepage’s Macbeth (Rating: ✭✭) vrooms onto the Avon Theatre stage with lots of hoopla and buzz but not much substance.

I’m guilty myself of contributing to the pre-opening attention. Back in 2018, I’d marvelled at Lepage’s Stratford staging of Coriolanus. And so when my editor at the Toronto Star asked if I wanted to interview five actors who were reuniting with Lepage for his biker gang-themed staging of the Scottish play, I said hell yeah. I thought it’d be fascinating to get a glimpse into the master director’s process with actors. Here’s that piece.

On paper, the idea of setting Shakespeare’s play in the violent and hierarchical world of the Quebec biker wars of the 1990s sounds thrilling. And at first it’s a blast to see a bunch of leather-clad characters (Michael Gianfrancesco designed the costumes) ride their souped up electric bikes across a stage to have a conversation. When the play’s main setting — a seedy motel that acts as a bunker — initially appears, being moved (presumably by stagehands) to reveal different rooms and vantage points, it’s also visually impressive. (Ariane Sauvé designed the set and props.) The filmic opening image, too, is haunting.

But Lepage doesn’t modulate or develop these scenes. There are too many examples of characters riding bikes to have a simple conversation. And that motel keeps twisting around, rarely giving a glimpse at something we haven’t seen before. These repetitive scenes add to the considerable running time of the Bard’s shortest play.

To be fair, there are some impressive bits of stage business. When two bikers carry out a hit at a gas station, some gas tanks catch flame. Those flames, in the very next scene, morph into the lighting of BBQs for the famous banquet scene. And Macbeth’s “Is this a dagger which I see before me?” sequence comes alive with some nice use of projections. Clever.

These are mere tricks, however, compared with what Lepage did in Coriolanus, where setting and props helped underline a point, or a character dynamic, in the script. Even seeing the Porter (Maria Vacratsis) wordlessly go to change the bloody sheets where Duncan has been murdered loses its impact; we saw a similar scene, filled with a lot more unspoken horror, in Dana H.

All of this would be forgiveable if Lepage and his impressive acting company had offered up first-rate performances. I don’t know if the director encouraged his company to undersell their dialogue, but most lines are delivered with so little energy and commitment that they’re barely perceptible.

The performances aren’t bad, necessarily, although one young actor, delivering lines that are often cut, needs much firmer direction. They’re just adequate and lost amidst all the visual stage business. Do we really need Macbeth (Tom McCamus) to snort coke before a famous soliloquy? Or for Lady M (Lucy Peacock) to deliver her mad scene behind walls?

I know Lepage and his Ex-Machina productions — this debut is described as a “collaboration” with them — often get tweaked as time goes by. And this production is already slated for a French language version next summer at the National Arts Centre.

Even when I caught it, about a month after opening, there had been some changes — the full cinematic opening credits, for instance, had been scaled back to the mere title. Hopefully, Lepage and his design team will have figured out some of the technical issues, most involving mirrors and reflections, that seemed wobbly at my performance. The Birnam Wood scene, which I won’t fully describe here, seemed merely tacky.

I’m not sure how much he can do with the overall concept, though. Some people are telling me that I need to have seen the HBO series Sons of Anarchy to fully appreciate this production. Really?

What the biker war setting does is cheapen and deflate Shakespeare’s masterpiece. I’m certainly not implying that you need a traditional production to make the play work, but you need more than the over-produced, often cumbersome concept we’re offered here.

In my interview with those five actors who returned for this production to work again with Lepage, Rooney mentioned a spare but evocative bilingual production of Romeo and Juliet he did with the director in Saskatoon in 1989.

“Even before he was a big international theatre star, he came up with ideas that were so simple yet powerful,” said Rooney. “There’s more money behind his productions now, but he’s still able to tell stories in this poetic and ingenious way. It’s always fun to see what he’s going to come up with.”

This Macbeth is missing that fun.

The Winter’s Tale continues at the Tom Patterson Theatre until September 27. Macbeth has been extended at the Avon Theatre until November 22. See info and get tickets here.

Want more Stratford? I reviewed Anne of Green Gables here, and I reviewed the musicals Annie and Dirty Rotten Scoundrels here.